Those Who Are Fit to Die

None are fit to die who have shrunk from the joy of life.

— Theodore Roosevelt, scribed on the walls of the Natural History Museum of New York City

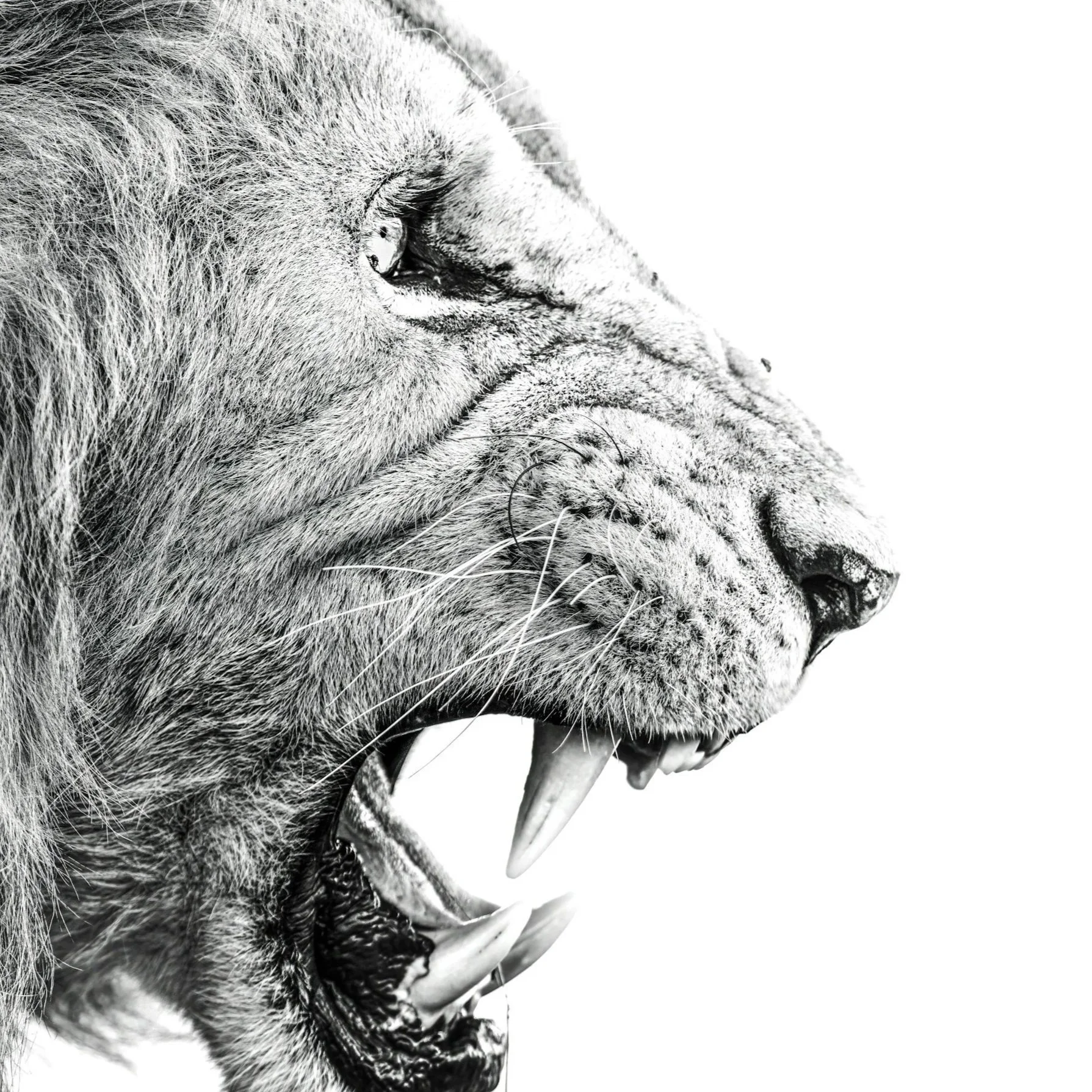

His muscles are taut and eyes glossy, mid-thought, frozen and still. Contemplative, I believe he might have been when he died, preserved in such a paused emotion. And maybe that’s why I sat with the lion for so long at the natural history museum, because while he was obviously beautiful, I truly wondered how many wanted to just be there with him. I had never seen a lion look so alive — not even in the zoo.

But I guess all museums curate the result — the Louvre with its aristocratic frescos and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía with memories of war — standing as monuments to what was once so palpable. It is clear, even with our desire to remember, that all things are meant to die, even those thoughts and figures we preserve in museums, even my cowardly lion. And so the failure of preservation is obvious: taxidermy will erode and memories will fade; what feels permanent is just delayed disappearance.

The Ethics of Witness

When I was younger, I believed deeply in the power of presence, perhaps because my parents attended every swim meet, every doctor’s appointment, every celebratory function held in my honor. Whether the crowd was cheering, the doctor was listening to my heartbeat, or I was receiving a participation ribbon, my mom and dad were there. None of those moments will make it into a history book. They will not hang in the Louvre or rest behind glass like relics of a species. But they felt like a rise into the excitement of life. I was not preserved — I was participating.

And so I wonder what it means now to sit before the lion and call it reverence. Am I part of the system that produces his stillness, or the one that once demanded his movement? I waited in line. I bought a ticket. I entered quietly and stood beneath curated light. My presence feels gentler than the rifle that ended him, but it is still part of the same story.

Why do I feel such tenderness for something that was killed for my education? Perhaps because I have a kitten of my own. Luna is six pounds and missing an eye, but in my mind she is as equal a predator and magnetic beast as any hundred-pound lion. When she stalks the edge of the couch, tail low and shoulders rolling, I see the same instinct that once lived in him. The difference is scale, not essence.

Maybe that is what unsettles me — not death alone, but proximity. The museum invites awe at a distance. Sitting with the lion felt less like observation and more like keeping watch. And yet I cannot ignore that my watch comes after the ending.

The Hunted

What makes me most uncomfortable is that the violence that preceded this lion has been erased, or perhaps refined into education. The plaque speaks of habitat and species and migration patterns. It does not speak of the moment breath left the body.

I sit beneath Roosevelt’s sentence and beneath the lion’s glass case, and I cannot ignore that both are monuments — one to a philosophy of vigor, the other to a body that once embodied it. The museum begins to feel less like a sanctuary and more like an archive of conquest — polished, well-lit, intellectually justified. Not simply a celebration of life, but a record of who had the power to end it and preserve it.

Perhaps that is what unsettles me. The lion’s stillness is not neutral. It is the result of someone else’s refusal to shrink. And I, reading the quote, buying the ticket, sitting in awe, inherit both legacies at once.

Till Death Do Us Part

If the measure is joy, who calculates it? If the standard is refusal to shrink, who decides what shrinking looks like? The lion did not retreat from the savanna. But the museum suggests that fitness has little to do with virtue and everything to do with survival. Only one body stands to be quoted. Only one is granted narrative.

Perhaps no one is fit to die, if fitness implies deserving. Death does not consult courage, does not reward vitality, or spare the timid or the bold. The lion’s strength did not negotiate his ending. Roosevelt’s vigor did not either. One was preserved in posture; the other in language.

When I think of my parents sitting in metal bleachers at swim meets, or of Luna with her feline claws and paws, I learn that I cannot rank lives by how strenuously they burned. Their worth was never in spectacle. It was in presence.

Maybe the question is not who is fit to die, but why we insist on making death a moral achievement. To say someone is “fit” is to imply that living must be proven, that joy must be demonstrated loudly enough to justify an ending. But most lives are not lived in conquest or climax. They are lived in rooms, in routines, in quiet repetitions that never reach the walls of a museum.

If that is shrinking, then shrinking is simply being human.